Benton County History

FOUNDING and EARLY HISTORY

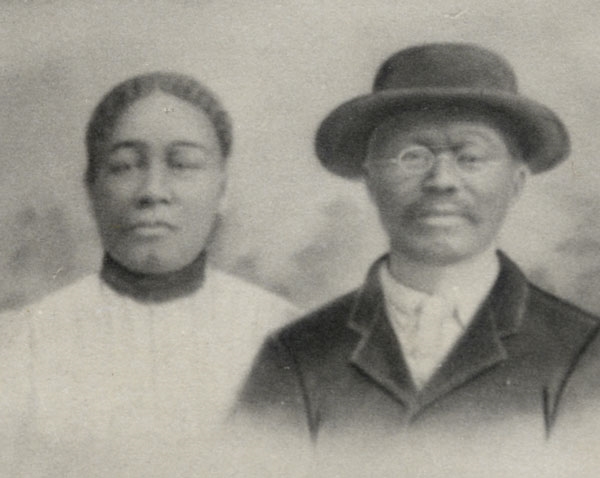

In 1870, Benton County was formed out of eastern Marshall and western Tippah counties. Black people owned land when Benton was established, and bought land throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. They also lost land to white people or were killed for their land.

JIM CROW and the 1940s

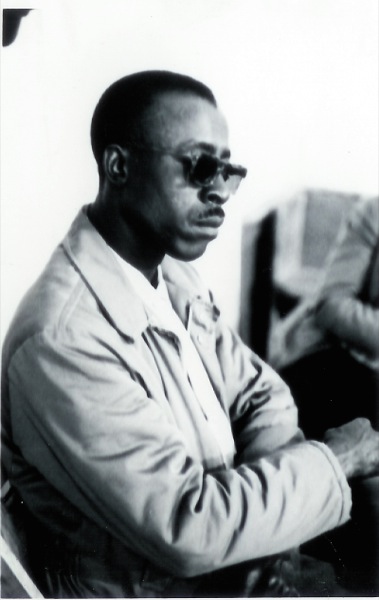

Throughout the 1940s, Mr. Henry Reaves headed a small group of black citizens who went to Mound Bayou for NAACP meetings and established a Citizens' Club, which focused on voter registration.

1964 and SNCC

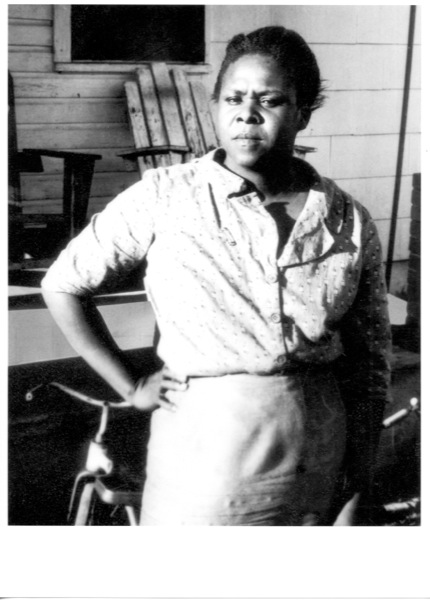

In June 1964, civil rights workers from the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) came to Benton County and worked with Henry Reaves and a revitalized Citizens' Club. They undertook activities such as voter registration, fair treatment by the government in agricultural programs, improving the black school, and school desegregation. Freedom Schools were established at Mount Zion and other churches and taught by civil rights workers. Even before 1964, many Black citizens of Benton County tried to register to vote. Almost all were turned down because they "failed" to interpret sections of the Mississippi Constitution to the satisfaction of the county registrar. On December 1, 1964, the Citizens' Club prevailed upon the US Justice Department to sue the Benton County registrar in federal court in Oxford. The registrar then permitted more Blacks to register, but still turned away 30%. On September 25, 1965, Benton County became the 5th and smallest Mississippi county to have a federal registrar appointed. By the end of 1965, about 1000 Black citizens were registered to vote, leaving some 200 unregistered. In June 1964, the Citizens' Club published the first issue of a mimeographed newspaper, the Benton County Freedom Train. The paper was edited by Beulah Mae Ayers. Many people were responsible for writing and distributing the paper. Sharecroppers working on whites' land would run out of the fields and grab a stack of papers whenever a civil rights worker's car passed by.

THE 1965 SCHOOL BOYCOTT and INTEGRATION

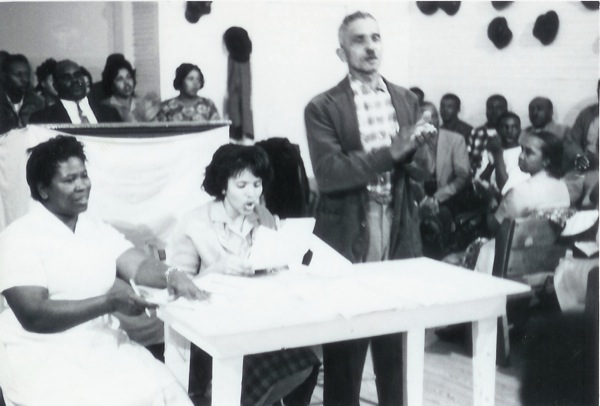

In January 1965, civil rights worker Aviva Futorian was arrested and jailed for attending a basketball game at Old Salem School, at the then all-black school. The principal of Old Salem, W.B. "Woody" Foster, asked Aviva to leave. When she refused, the sheriff, superintendent, and State's Attorney came into the gym and arrested her. School children going home for the day quickly spread the news, and anger at Foster (who had ignored requests by the Citizens' Club to improve the standards of Old Salem on numerous occasions) was quickly solidified by students and their families. On February 1, 1965, the Citizens' Club met with the all white school board and asked them to replace Foster with the vice-principal at Old Salem, Lloyd Peterson. They also outlined the poor conditions at Old Salem and made several other requests for improving the school, such as establishing a library and hiring a librarian.

When the board offered the Citizens' Club a deal in which it would agree to the Citizens' Club's demands in return for their agreement to "stay away from the white schools," the Citizens' Club refused. On March 9, 1965, they voted to boycott the school. 1,070 of 1,200 total students stayed away on the first day.

Five school bus drivers were fired for supporting the boycott. On the day of their firing, they went into Ashland and integrated an all white cafe.

Ultimately, the school board gave in to the Citizens' Club's demands and fired W.B. Foster. But the white school board, under the leadership of county attorneys Hamer McKenzie and John Farese, made Mr. Foster, in May 1965, sue the Citizens' Club, the Freedom Train, and Aviva Futorian for libel for their criticism of him. He sought $600,000 in damages. Judge Walter O'Barr awarded Foster $60,000. Later, the Mississippi Supreme Court reversed the verdict and declared the defendants had a right to publicly criticize a public figure. The next time O'Barr ran for judge, he sent a letter to all black residents of Benton County asking them to let bygones be bygones and vote for him. They turned him out of office. In June 1965, 44 parents and 107 students filed suit against Benton County to desegregate its school system. The following month, the federal court ordered the school system to initiate a "freedom of choice" desegregation plan. This was a staggered system of allowing black children to "choose" to attend the white school (Ashland Elementary/Middle/High School). The first year, the plan applied to the 1st, 10th, 11th and 12th grades. As each year passed, it applied to more grades. In response, In August 1965, crosses were burned in front of the Citizens' Club office, at the homes of students integrating the school, and civil rights' workers homes among others. In October, there was attempt to burn down the Citizens' Club office.

AFTER the MOVEMENT

The last year of freedom of choice was 1970. After that, Old Salem became the elementary school for the northern part of the county, and Ashland became the high school for the northern part of the county. In the southern part of the county, there was one school, Hickory Flat Attendance Center. Today, Ashland High School is over 90% black, and Hickory Flat Attendance Center is over 90% white. Though school scores have been average or below average, they show signs of increasing. A new superintendent, Patrick Washington (the county's first black person to hold the office) has outlined an ambitious plan to improve the system.

A dedicated group of citizens, many of them veterans of the civil rights movement, continue to work for the betterment Benton County.